Tennessee Williams, F Scott Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Cheever, Carver, Berryman… Six giants of American literature – and all addicted to alcohol. In an edited extract from her new book, The Trip to Echo Spring, Olivia Laing looks at the link between writers and the bottle.

In the small hours of 25 February 1983, the playwright Tennessee Williams died in his suite at the Elysée, a small, pleasant hotel on the outskirts of the Theatre District in New York City. He was 71: unhappy, a little underweight, addicted to drugs and alcohol and paranoid sometimes to the point of delirium.

The next day, the New York Times ran an obituary claiming him as “the most important American playwright after Eugene O’Neill”, though it had been two decades since his last successful play.

He was also a kind, generous, hard-working man, who rose at dawn almost every morning of his life, sitting down at his typewriter with a cup of black coffee to produce what would amount to well over 100 short stories and plays.

At the same time, he was a lonely, depressed alcoholic who managed by degrees to isolate himself from almost everyone he loved.

Things got worse in 1963, when Williams’s long-term partner Frank Merlo, nicknamed the Little Horse, died of lung cancer. After that, he was far gone and out, barely perpendicular against the current, buoyed on a diet of coffee, liquor, barbiturates and speed.

Hardly any wonder he found speech difficult, or kept toppling over in bars, theatres and hotels. Each year he put on a new play, and each year it failed, rarely lasting a month before it closed.

Two years before he died, Williams was interviewed in the Paris Review. He talked about his work and the people he had known, and he touched too, a little disingenuously, on the role of alcohol in his life, saying: “O’Neill had a terrible problem with alcohol. Most writers do. American writers nearly all have problems with alcohol because there’s a great deal of tension involved in writing, you know that. And it’s all right up to a certain age, and then you begin to need a little nervous support that you get from drinking.”

While not all of this statement is wholly to be believed, it’s true that Williams was by no means the only alcoholic writer in America, or anywhere else for that matter. Ernest Hemingway. F Scott Fitzgerald. William Faulkner. John Cheever. Patricia Highsmith. Truman Capote. Dylan Thomas. Jack London. Marguerite Duras. Elizabeth Bishop. Jean Rhys. Hart Crane.

These are among the greatest writers of our age, and yet, like Williams, their addiction to alcohol damaged their creativity, ravaged their relationships and drove many of them to death.

Discussing Edgar Allan Poe, Baudelaire once commented that alcohol had become a weapon “to kill something inside himself, a worm that would not die”. In his introduction to Recovery, the posthumously published novel of the poet John Berryman, Saul Bellow observed: “Inspiration contained a death threat. He would, as he wrote the things he had waited and prayed for, fall apart. Drink was a stabiliser. It somewhat reduced the fatal intensity.”

In Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Williams explains the desire even more succinctly. Towards the end of the play, Brick, the former football hero, tells his father that he needs to keep drinking until he hears “the click…This click that I get in my head that makes me peaceful. I got to drink till I get it.” Horrified, Big Daddy grabs his son’s shoulders, exclaiming: “Why boy, you’re alcoholic.”

Most of the previously mentioned writers died in middle age, and the deaths that weren’t suicides tended to be directly related to the years of hard and hectic living. At times, all tried in varying degrees to give up alcohol but only two succeeded, late in life, in becoming permanently dry.

These sound like tragic lives, the lives of wastrels or dissolutes, and yet these six men – Tennessee Williams, Ernest Hemingway, F Scott Fitzgerald, John Cheever, John Berryman and Raymond Carver – produced between them some of the most beautiful writing this world has ever seen.

I wanted to know how their writing and drinking had intertwined, and so in 2011 I took a trip across America. Over the course of a month I travelled by plane and train across the country, drifting from New York to New Orleans, Key West, St Paul and Port Angeles.

I chose these places because they seemed to serve as staging posts, in which the successive phases of alcohol addiction had been acted out. By travelling through them in sequence, I thought it might be possible to build a kind of topographical map of alcoholism, tracing its developing contours from the pleasures of intoxication through to the gruelling realities of the drying-out process.

Tom had been a sickly, delicate boy, and as a teenager began to suffer the panic attacks that would dog him until the very last days of his life. At first he used to self-medicate by pacing the streets of St Louis or swimming frantic lengths in a nearby pool. But as he grew older and moved to New York, sex and alcohol became his preferred methods of managing stress.

In his autobiography, Memoirs, he remembered how after drinking wine “you felt as if a new kind of blood had been transfused into your arteries, a blood that swept away all anxiety and all tension for a while, and for a while is the stuff that dreams are made of”.

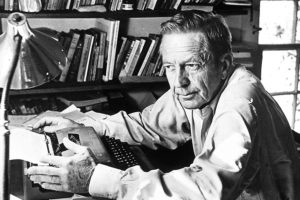

Short-story master John Cheever in 1975, which was the year he was admitted to a treatment centre and afterwards declared: ‘I came out 20lb lighter and howling with pleasure.’ He never drank again and died of cancer in 1982. Photograph: Bernard Gotfryd/Getty Images

Short-story master John Cheever in 1975, which was the year he was admitted to a treatment centre and afterwards declared: ‘I came out 20lb lighter and howling with pleasure.’ He never drank again and died of cancer in 1982. Photograph: Bernard Gotfryd/Getty Images

He was by no means the only writer who used alcohol in this way. The same trick was employed by John Cheever, one of the greatest short-story writers of his or any century. Cheever fascinated me because he was, in common with many alcoholics, a helpless mixture of fraudulence and honesty.

Cheever couldn’t shake the sense of (as seeing himself as) being an impostor (artiste) among the middle classes. Writers, even the most socially gifted and established, must be outsiders of some sort, if only because their job is that of scrutiniser and witness. All the same, Cheever’s sense of double-dealing seems to have run unusually deep.

Who wouldn’t drink in a situation like that, to ease the pressure of maintaining such intricately folded double lives? He’d been hitting it hard since he first arrived in New York, back in 1943. Even in the depths of poverty he managed to find funds for nights that might, head-splittingly, take in a dozen Manhattans or a quart apiece of whiskey.

Alcohol was an essential ingredient of Cheever’s ideal of a cultured life, one of those rites whose correct assumption could protect him from the persistent shadows of inferiority and shame.

Instead, it did just the opposite. By the late 1950s, Cheever was using the word alcoholism to describe his behaviour, writing grimly: “In the morning I am deeply depressed, my insides barely function, my kidney is painful, my hands shake, and walking down Madison Avenue I am in fear of death. But evening comes or even noon and some combination of nervous tensions obscures my memories of what whiskey costs me in the way of physical and intellectual wellbeing. I could very easily destroy myself. It is 10 o’clock now and I am thinking of the noontime snort.”

In order to understand how an intelligent man could get himself into such a dire situation, it’s necessary to understand what a glass of champagne or shot of scotch does to the human body.

Alcohol is both an intoxicant and a central nervous depressant, with an immensely complex effect upon the brain. A single drink brings about a surge of euphoria, followed by a diminishment in fear and agitation caused by a reduction in brain activity. Everyone experiences these effects, and they are the reason alcohol is such a pleasurable drug; the reason why, despite my history, I too love to drink.

But if the drinking is habitual, the brain begins to compensate for these calming effects by producing an increase in excitatory neurotransmitters. What this means in practice is that when one stops drinking, even for a day or two, the increased activity manifests itself by way of an eruption of anxiety, more severe than anything that came before. This neuroadaptation is what drives addiction in the susceptible, eventually making the drinker require alcohol in order to function at all.

As it gathers momentum, alcohol addiction inevitably affects the drinker, visibly damaging the architecture of their life.

Not everyone who drinks, of course, becomes an alcoholic. The disease, which exists in all quarters of the world, is caused by an intricate mosaic of factors, among them genetic predisposition, early life experience and social influences. Jobs are lost. Relationships spoil. There may be accidents, arrests and injuries, or the drinker may simply become increasingly neglectful of their responsibilities and capacity to provide self-care.

Conditions associated with long-term alcoholism include hepatitis, cirrhosis, gastritis, heart disease, hypertension, impotence, infertility, various types of cancer, increased susceptibility to infection, sleep disorders, loss of memory and personality changes caused by damage to the brain. More stress, of course: to be drowned out in turn by drink after drink after drink.

F.Scott Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda

F.Scott Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda

This is where the black stories start. This is where you find the bloated, feuding Hemingway of the later years, his liver so swollen it protruded from his gut like a long leech. This is where you find F Scott Fitzgerald, washed up in Baltimore in the mid-1930s, his wife in an asylum, writing bad stories drunk and crashing his car into town buildings. And this is where you find the poet John Berryman, esteemed professor, breaking his bones and vomiting in strangers’ cars.

I hate these stories. They’re true and they’re also untrue, and profoundly distorting. What I discovered as I travelled was how ambiguous and contradictory the issue of writers and alcohol really is. On the one hand, there’s dissolution and degradation, and on the other there’s dogged labour, compulsive honesty and the production of enduring art.

Reading Tennessee Williams’s diaries while he was writing Cat on a Hot Tin Roof reveals a man in crisis, so profoundly addicted to alcohol that he carried a flask of whiskey wherever he went. And yet the play he produced is a miracle of truth-telling. It seems impossible that in the midst of such confusion and self-harm,

Williams was able to produce a play like Cat, with its uncompromising portrayal of the drinker’s urge to evade reality. And yet he retained in some unobliterated part of himself the necessary clarity to set down on paper a portrait of the self-deceiving nature of the alcoholic.

He was not the only one, by any means. From Berryman’s Dream Songs to Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night and Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls, there exist dozens of works of art in which an alcoholic writer reflects on their own disease; a disease, furthermore, that is hallmarked by distortions in thinking, particularly denial.

When I travelled to Key West to visit Hemingway’s house, I kept thinking in particular about a line in For Whom the Bell Tolls that compares alcoholism to “a deadly wheel… it is the thing that drunkards and those who are truly mean or cruel ride until they die.”

These stories weigh on me, and yet an alcoholic can stop drinking.

I knew it from my own childhood, and I knew it from my reading. My mother’s ex-partner got dry at a treatment centre she still describes as a hellhole, and came back into our lives sober. John Cheever also managed it. “I came out of prison 20 pounds lighter and howling with pleasure.”

The writer whose sobriety most interested me, however, was Raymond Carver. I’d come across his poems long ago, and been struck by the praiseful way he wrote about his second life: the one in which alcohol was no longer the dominating force.

It’s almost impossible to overestimate the hardship of Carver’s early adulthood, in which he struggled to educate himself and get food on the table while stealing every spare minute in which to write. In such straitened circumstances, it’s not difficult to understand why alcohol might have begun to seem like an ally, or else a key to a locked door.

There’s no doubt the odds were stacked against him; but nor is there much doubt that he became, six days out of seven, his own worst enemy. The things Carver did seem so senselessly self-destructive. One Raymond – Good Raymond, I suppose – would get on to a master’s programme, or find a decent job, and the other Raymond, the perverse, malevolent one, would somehow conspire to mess it up.

At the same time he was unreliable, paranoid and violent; by his own description a bankrupt, a cheat, a thief and a liar. As for creativity, as he approached the height of his drinking he could barely write at all.

In 1976 he checked into Duffy’s, a private treatment centre in Napa. Unsurprisingly, he was back again weeks later, checking himself in on New Year’s Eve. It was his last pass through formal treatment. That spring he left his family and rented a house alone, overlooking the Pacific. For the next few months he went to AA meetings and tried, not always successfully, to maintain his balance on the wagon.

Slowly, over the next two years, he backed away from his family, whose ongoing troubles he felt certain were capable of scuttling his recovery. For a while he barely wrote, and then the new stories started coming; stories infused with “little human connections”; stories he’d “come back from the grave” to write.

Carver once said he didn’t believe in God, “but I have to believe in miracles and the possibility of resurrection. No question about that. Every day that I wake up, I’m glad to wake up.”

I stood by (Carver’s) grave for a long time, thinking about alcohol, and the trouble it brings. There’s a saying in AA that addiction isn’t your fault but recovery is your responsibility.

It sounds simple enough but making that step is about as easy as standing up and dancing on a sheet of black ice. In Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Brick says to his dying father: “It’s hard for me to understand how anybody could care if he lived or died or was dying or cared about anything but whether or not there was liquor left in the bottle.”

Imagine feeling like that. And then imagine sitting down at your typewriter every morning, day after day, year after year. It was Cheever’s words I thought of then. In 1969, when he was still in the thickets of his own addiction, he was asked if he felt godlike at the typewriter.

What he answered seemed to me to sum up the ambiguity of writers and alcoholism, the difficulty of passing judgment on lives at once so troubled and so blessed. “No, I’ve never felt godlike,” he said. “No, the sense is of one’s total usefulness. We all have a power of control, it’s part of our lives: we have it in love, in work that we love doing. It’s a sense of ecstasy, as simple as that… In short, you’ve made sense of your life.”

© Olivia Laing. This is an edited extract from The Trip to Echo Spring, published by Canongate